"A library implies an act of faith." Victor Hugo, novelist

"A great library easily begets affection, which may deepen into love." Augustine Birrell, author

The Madison Public Library is a place of magic. The library can spark a new idea from thin air, transport readers in time and space, and unlock innumerable mysteries. For more than one hundred and twenty-five years, the Madison Public Library (MPL) has embodied the radical assumption that society should provide its members the means to independently continue their education and to satisfy some of their recreational needs. It has offered opportunities to people of all ages to stretch their minds and nourish their souls, and often access to luxuries otherwise unaffordable. MPL has been the only major public institution in Madison with a mandate to provide services for the entire life span of its clients.

MPL has experienced enormous changes since its founding. The library has grown from operating in one small room in city hall to offering service at the Central Library and eight library branches spread across the city. The first MPL librarian had no experience working in a library whereas today’s staff are highly skilled and often have specialized training in areas like reference services. Children under fifteen years of age were prohibited from using the original library while the contemporary Central Library has an entire room devoted to meeting the needs of children of all ages. The ever-present objective of providing the right book for the right person has now expanded to include magazines, newspapers, microfiche, videotapes, compact discs, and more.

Though the library has grown and changed in innumerable ways since its founding, the staff and board have been driven from the outset to provide the best service possible. The unvarying and perhaps most important philosophy that has guided library policy has been the commitment to reach as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. In 2000, we take this value for granted, just as we expect the library to be open during most of our waking hours, to satisfy many of our educational and recreational desires, and the librarians to provide courteous and competent assistance. The fact that history can justifiably lead us to expect MPL to continue to provide outstanding service and to meet many of our needs is a testimony to the achievements of MPL staff over the past one hundred and twenty five years.

The stories from the early days of the library are departure points on a road map for many of the directions MPL has subsequently traveled. The speeches at the library's opening ceremony articulate the vision that library staff and board members have zealously pursued for more than a century: to create a library for all people, to operate as an educational institution for children and adults, and to serve as a tool for recreation and inspiration. The excerpt from the "Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Directors" again emphasizes the educational and recreational functions of the library, but is expressed with an elitist and mistrustful attitude toward the library's patrons characteristic of many of the middle class reformers who formed libraries in the nineteenth century. The city health officer's report describing the fears of contagion spread by books reflects librarians’ concern for the well-being of patrons and highlights the differences between the state of the world during the early days of the library's existence and modern times. The Iroquois Fire story represents one of the tales of high drama that periodically have occurred in the library's history, and again underscores the significantly different context in which the early library operated. Finally, the selection on the outreach campaign to the Maple Bluff Country Club caddies exemplifies MPL's historic commitment to provide service to any population that can benefit from library assistance.

In the Beginning, There Were–Beans!!

It was the world of our grandparents, great grandparents, and great-great grandparents. It was a world without electricity and a world in which women could not vote. It would soon be a world without a tall soldier with yellow hair and mustache named George Armstrong Custer, who would be killed at Little Bighorn one year hence.

Madison, Wisconsin, 1875 — a small town of between 9,000 and 10,000 people. Victorian buildings with flickering gaslights and oil lamps lined the streets. Cattle periodically strayed from the pastures and roamed the muddy streets. There were livery stables that did the business of taxis and buses, wagon and carriage makers, and dealers in spirit lamps. Singing around the piano was a favorite pastime for young people. Outdoors there was skating in the winter and sailing and croquet in the summer.

The 1875-76 Madison City Directory described Madison as follows:

"Madison is the seat of justice of Dane County, and capital of the state of Wisconsin. …The city is pleasantly situated on an isthmus about three-fourths of a mile wide, between lakes Mendota and Monona, in the center of a broad valley, surrounded by heights from which it can be seen at a distance of several miles. The streets are well provided with substantial side-walks, usually kept in good repair, and afford many attractive promenades and drives. The capitol building is a beautiful stone structure, standing on an eminence of seventy feet above the level of the lakes, in the center of a public park of fourteen acres, and contains the very valuable State Historical Library…"

In 1875, Madison had two daily newspapers: the morning Madison Democrat and the afternoon Wisconsin State Journal. Stories of the day included descriptions of "Whiskey Seizures" in St. Louis, "The National Temperance Convention" in Chicago, and President Grant’s decision not to seek a third term of office. There were advertisements touting "Chicago Property Cheap," "Young Men Wanted to Learn Telegraphing," "D.C Foote's Cigars All Made by Hand," "Piles Cured," and "Wallace's Tonic Stomach Bitters," the latter described as a "perfect eradication of all Bilious Diseases arising from a foul stomach."

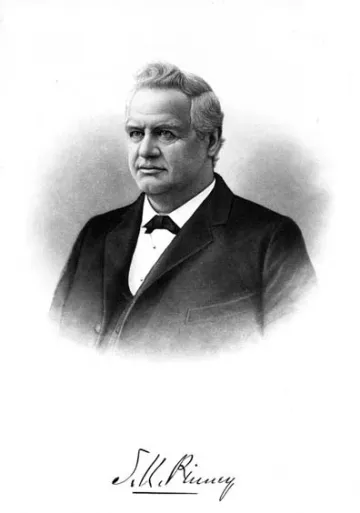

In 1875, Mayor Silas U. Pinney worried that tourists would stop coming to Madison because of the great quantities of garbage in the streets. Roaming dog packs periodically attacked horses and Madison exporters began supplying ice from the clean lakes to the brewing industries in Chicago and Milwaukee.

The 1875-76 Madison City Directory Classified Business section informs us that Madison possessed eight bakeries, eight barber shops, two bath rooms (including one "Turkish"), two billiard halls, nine blacksmiths, five carriage and wagon makers, two book binders, five breweries, two bowling alleys, two coal yards, three dentists, eight dress makers, two gunsmiths, twenty-six hotels, two insurance agents, four justices of the peace, two marble yards, one occulist and aurist, four photographers, four real estate agents, two restaurants, thirty one saloons, three sewing machine agents, one soap and candle manufactory, one telegraph company, three undertakers, and one vinegar factory. The city included such diverse organizations as the Knights of Pythias, the Odd Fellows, The Druids, the Madison Scheutzen Club, the Young Men's Literary Society, Turners, the Grand Army of the Republic, and public buildings such as the Masonic Hall, Opera House, and Good Templar’s Hall.

In 1875, The University of Wisconsin-Madison library was open on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday for two hours each afternoon. In a time when the debate was raging over separate schooling for the sexes versus co-education, only "gentlemen" could use the library on two of those days and young "ladies" on the other two. In their report the preceding year, the UW Board of Visitors (advisory board on needs of the university) expressed what subsequently became a classic statement regarding the housing and holdings of the UW Library: "..the Library of the University is a disgrace to the state." Conversely, by 1876 the State Historical Society Library was the pride of Madison and had the largest collection of books west of Washington DC (65,000 items).

It was in this world on May 31, 1875, that Madison's first public library, the Madison Free Library (MFL), opened in two rooms on the second floor of the former City Treasurer's office in City Hall, located on the Capitol Square at the intersection of West Mifflin Street and Wisconsin Avenue. The library of the Madison Institute, forerunner of the MFL, had previously occupied that same office since 1866 and contributed its 3,170-volume collection to the new library. Citizens were invited to come to the opening and bring a valuable book to contribute, and indeed they added 200 volumes to the collection.

On the following day, the Madison Democrat announced the inauguration of the library with triumphant headlines:

"Pioneer Public Library"

"Madison Leads State"

"An Auspicious Opening"

"Large Audience at City Hall"

"Many Additions of New Books"

The related article described the festive opening ceremony in great detail, including giving a favorable review for the "Lake City Cornet Band" which "struck up a lively air" and had "excellent execution." The Madison Democrat also reproduced the full texts of several lengthy speeches presented at the ceremony including those from J.C. Ford, President of the Board of Directors of the Library, Mayor Silas U. Pinney, State Superintendent of Schools Edward Searing, University of Wisconsin President John Bascom, and UW Professor of Humanities and Greek James D. Butler. Ford spoke on the library’s public but non-political nature and the need for citizen support to create a library for all people, young and old, rich and poor. Mayor Pinney emphasized the library’s role as a young people’s educational institution. Superintendent Searing discussed the prospects for adult education, and Professor Butler delivered a philosophical speech that described the library as a tool for amusement, instruction, and inspiration.

Excerpts from Mayor Pinney's and Professor Butler’s speeches provide a flavor for the event and the speaking style of the times:

Mayor Pinney's Address:

Image

"Mr. President, Ladies, and Gentlemen, the founding and opening of a free library, which is to diffuse its advantages and confer its blessings on all alike, whether rich or poor, of whatever condition, is an enterprise and an event of marked public interest and importance.

The successful establishment of such an institution cannot but be regarded as an era in the history of this city, securing as it does all those signal advantages and beneficent influences which such and all similar institutions, when judiciously conducted, necessarily confer…"

Professor Butler's Address:

"My subject is LIBRARIES AS LEAVEN, or the relation of Libraries to the increase and diffusion of knowledge.

What is a Library? It is the knowledge of all brought within the reach of each one. It is an expanded encyclopedia, or the books which are, or ought to be, consulted in compiling a perfect encyclopedia.

Human knowledge and hence the books in which it is treasured up is divided by some authors into forty departments. I have their names here all written down but I dare not read them. You would give no more quarter to such a catalog than the lover gave to the mercantile inventory of his sweetheart's charms, when itemized as "two lips indifferent red," "Two gray eyes with lids to them," and so on…"

At the March 16, 1875, Library Board of Directors meeting, the board had adopted its rules. The library would be open from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., and 2:30 to 5:30 p.m. on all days except Sundays and holidays. The library also would be open on Wednesday and Saturdays evenings from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m. in order to provide maximum access to books. All users had to sign an obligation in which they promised to obey the library rules. Children under fifteen years of age were not permitted in the library, although it was acceptable for their parents to obtain books for them.

At the March 30, 1875, Board meeting, the directors elected Virginia Robbins librarian and agreed to pay her $400 per annum, payable quarterly. This position had attracted five applicants ("young ladies") and the selection process took eleven ballots before Miss Robbins received a clear majority. While home and children were still the woman’s domain in 1875, the aura of respectability for women in the work force had been established, and teaching and library work were considered appropriate careers for young women. Miss Robbins would function primarily as a clerk to dispense requested books. She would list the books and supervise the room. Book selection and arrangement were the Board’s responsibility. The librarian would execute only those tasks the Board left for her.

Miss Robbins took over the office of the city treasurer in the City Hall; the "Library Room" as it was by then called. When the library opened, she used big ledgers to keep track of which books were checked out and by whom. Every reader had his or her name on a page. Each book they took out was listed on that page along with the date they took it out, the day they returned it, and the condition it was in.

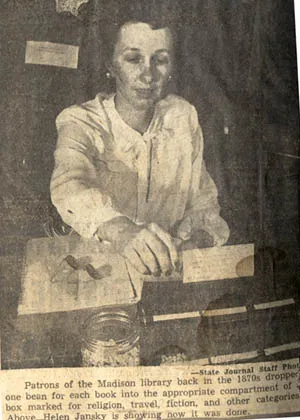

Virginia Robbins kept track of the number of books borrowed with beans. There was a collection box with sections labeled history, literature, religion, travel, fiction, and science. When patrons checked out a book, they dropped a bean in the proper compartment of the box. Sometimes when patrons neglected to drop their beans, Miss Robbins put two or three extra beans in the boxes to keep the count as closely accurate as possible.

We can only speculate why she initiated this "bean counter" procedure. Either the board of directors or Miss Robbins herself wanted to collect data on the types or quantities of materials checked out. Perhaps the board specifically mandated it because they felt such information would provide useful ammunition in the future to convince the politicians and general populace that the library was being heavily used and therefore worthy of continued support. It had only been during the preceding year that Mayor Pinney had persuaded the fiscally conservative City Council to establish the free library. Documenting the circulation of books might help convince the reluctant council members to continue funding in the future. Or perhaps it was a means of tracking trends in patron readership so that the library could better meet the reading needs of the public. Maybe, however, Miss Robbins took to heart Professor Butler's contention that the library should serve as a source of amusement and she thought patrons might enjoy tossing beans into boxes!

City Hall

The City Hall building that served as MFL's first home enjoyed a rich and varied history. At different points in time, it housed a fire station, a theater, and even a saloon. Among some of the most notable characters who entertained from the City Hall’s third floor stage were Horace Greeley, Tom Thumb, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The original ordinance to establish a "Free Public Library and Reading Room"

"Ordinance for the Organization of a Free Public Library in the City of Madison. The Common Council of the City of Madison do ordain as follows:

Sec.1. That in pursuance of and by virtue of an act of the legislature of the state of Wisconsin entitled 'an act authorizing cities and villages to establish Free Public Libraries and Reading Rooms, approved Mar. 21st, 1872, there is established for the use of the inhabitants of the City of Madison, to be known as the Madison Free Library.

Sec. 2. There shall be provided and set apart under the direction of the City Clerk, rooms in the City Hall building for the reception of any books that may be donated or purchased for such Library and for use as a Reading Room until a permanent location is otherwise provided.

Sec.3. This ordinance shall take effect and be in force from and after its passage.

Approved Nov. 21st, 1874.

John Corscot, Clerk, S.U. Pinney, Mayor."

Different Strokes for Different Folks: "Library Lends Books to Caddies; Youngsters at Golf Links Supplied with Good Reading

More than two decades after the library board had expressed concerns about the "frivolity" of patrons, the library staff identified a population who indeed were passing their time in an activity even worse than "dangerous idleness." This recognition caused the librarian to undertake a most unusual outreach campaign. In July 1903, the MFL launched a project that combined its desire to reach out to underserved populations with its early missionary zeal to keep youth reading high quality, "moral" literature. An article that appeared in the July 28, 1903, edition of The Wisconsin State Journal describes this effort:

"The caddies at the Maple Bluff Golf Club are now supplied with books from the city library. It was noticed that many of the youngsters who follow the golf enthusiasts about the links had a fondness for literature with a yellow tinge and this tendency has been admirably counteracted by the sending of forty story books to the club house. The books are read with great eagerness. Bound volumes of the Youth's Companion and St. Nicholas are also sent which the boys read during their leisure moments. The books are in charge of Mrs. Swineford, apprentice librarian.

On some days there are as many as 20 caddies at the links and often they are not busy carrying the clubs so the books fill their spare time to good advantage. 'The books and magazines are read with great pleasure,' says Mrs. Swineford, 'and it will not be long before we have to get others from the library to take their place, so eagerly are they received’."

How Madisonians Avoided Being "Swallowed Up by Frivolity, Ennui, Dangerous Idleness, and Mental Vacuity"

"When I read a good book…I wish that life were three thousand years long." Ralph Waldo Emerson, poet

In 1872, the Wisconsin legislature passed a bill permitting municipalities to collect taxes to support a public library. Within a year, members of the Madison Institute, the association that had initiated the majority of literary activities in Madison since 1853, considered the formation of a public library in Madison. After Silas U. Pinney, a long-time member of the Institute was elected Mayor of Madison in April 1874, momentum began to gather to establish a public library. On November 21, 1874, the City Council passed an ordinance to form a free library and on April 14, 1875, the Madison Institute officially became the Madison Free Library.

The state public library law had stipulated that the mayor or executive was to appoint a board of directors to govern the affairs of the library. Hence, on January 4, 1875, nine men appointed by Mayor Pinney to the Library Board were confirmed by the City Council. Seven of these nine city leaders had been active in Madison Institute affairs. One director, John R. Blatzell, would become the mayor of Madison. Eight of the nine would serve on the library board for at least ten years and the ninth for five years. There has never been the same continuity of leadership and supervision provided by the library’s board of directors since the tenure of that initial group.

The board enacted and enforced the library's rules and regulations, selected and arranged the books, and oversaw all major functions of the library. They also provided the philosophical underpinnings of the institution. They believed the library should teach people of all classes about American culture, refine their manners, improve their morals, and expand their intellect. The library provided service, in part, to prevent the general public from spending their free time foolishly. The "Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the Free Library and Reading Room of the City of Madison, July 1, 1879," the earliest annual report still in existence, reflects this mistrust for how library patrons managed their leisure:

"…There are two very important objects to be steadily kept in view in a properly organized and conducted free library. The first is, to supply the people with rational amusement by an adequate number of entertaining books, which will enable them agreeably to pass the time, which otherwise would be swallowed up by frivolity, ennui, mental vacuity or something even worse. Man is so constituted, that after work, he needs and will have amusement of some kind, and it is better that such amusement should be innocent, and probably a source of new ideas, new emotions, and noble sentiments, and a wider knowledge of mankind and nature.

The books, which are ordinarily read for amusement, are novels, poems, and works of wit and humor. The novel, if good and of the better class, is not the moral delinquent it is commonly supposed to be in certain quarters…. Better the poor, dull and harmless novel than mental torpor or dangerous idleness-better the impossible and absurd heroes and heroines than gossip and scandal…"

During the Civil War, Judge Arthur Braley, one of the original board members, permitted the Madison Institute to store its library and papers in his law offices. These books eventually formed the core of the original collection of the Madison Free Library. He also hosted Westport native Ella Wheeler Wilcox in his home at 422 N. Henry Street when she said the now famous quote, "Laugh and the world laughs with you, cry and you cry alone."

Using the Water from Madison's Lakes: Speculations about Library Expenditures in 1879

The "Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Directors" of the library included the following list of the receipts and expenditures from that fiscal year:

Balance on hand, July $1,406.38 Appropriations by the common council $1,500.00 Fines, etc. $33.57 Total Receipts $2,939.95

The expenditures for the same period were as follows:

Services, salary of Librarian, etc. $444.00 Books $708.41 Binding, etc. $95.83 Fixtures, etc. $120.15 Insurance $25.00 Printing $18.75 Ice $6.50 Total expenditures $1419.94 Balance on hand July 1, 1879 $1520.01

In 1945, Capital Times columnist Alexius Baas wrote a seven-part series presenting the history of the MFL in his column "All Around the Town." In the September 30, 1945, column, his speculation about one of those expenditures highlights the vast ecological differences between the Madison of 1875 and 1945:

"I WONDERED as I read the above what they wanted of ice! Maybe it was for the old fashioned water coolers of those days when they took the ice from our Madison lakes and dumped it direct into the cooler without endangering any one's health. That was before the days of 98 per cent pure sewage effluent-and the lakes were still unpolluted. But note that the library was a going concern. They kept the city's appropriation intact."

Books Spread Infectious Diseases: The Great Scarlet Fever Scare of 1886

The marked difference between Madison in the nineteenth century and in later years also was evident in health issues as they related to library matters. In 1886, the contagion potentially spread by books was of great concern to MFL librarian Minnie Oakley. In the "Second Annual Report of the Health Officer, City of Madison, 1886," Dr. F.H. Bodenius expressed his gratitude to Miss Oakley for her vigilance in monitoring the threat of spread of contagion to library patrons:

"In May I was notified by the Librarian of our City Library that a book was returned to the library that had been in a house infected with scarlet fever. At the same time the question was propounded: Is there any way in which we could inform ourselves of the names and localities of families afflicted with some contagious disease, so that we might prevent books from becoming infected?

After consultation with the Librarian, it was agreed upon that all names and localities of families afflicted with any contagious disease should at once be reported to her, and this has been done the remainder of the year. Every one knows how easily contagious diseases may be spread by books used by patients. We owe Miss Minnie Oakley, the efficient Librarian, our thanks for her carefulness and promptness in reporting the case immediately."

Nearly twenty years later, the concern about the contagion spread by books remained strong. On October 31, 1905, the Wisconsin State Journal lamented the library's lack of equipment for fumigating books that had been in homes where there had been contagious diseases. Fortunately, the soon-to-be opened new library would have a place in the basement for the fumigation of the books.

In 1940, the concern about contagion and books was focused on tuberculosis in particular. The Laws and Rules of the Wisconsin State Board of Health regarding books stated,

"In cases where it is essential to disinfect books which have become infected the following requirements must be followed. Library books and school books which have been in a quarantined home should be withheld from circulation until they have been exposed to direct sunlight for a period of 15 days, opened daily in such a manner that the maximum number of pages will be reached.

Books used by a tubercular person should be burned or withheld from circulation until they have been exposed to direct sunlight for a period of 90 days, open daily in such a manner that the maximum number of pages will be reached.

Fumigation of books. The use of formaldehyde for fumigation is not effective."

In 1943, the Wisconsin Statutes stated that "library books shall not be taken into or returned from a home where such disease (dangerous communicable disease) exists or has recently occurred unless thoroughly disinfected by or under the direction of the local health officer, and may be burned by such officer."

The National Tuberculosis Association published a brochure in 1943 on "Home Care of Tuberculosis" which addressed the question of books and tuberculosis. The pamphlet included the question "Do my books have to burned?" with the response,

"No, not if your are careful to keep them clean. Sun and air them for several hours, for three days in succession, fanning out the pages, and keep out of use for a week. If soiled by sputum, they must be burned."

The Iroquois Fire Disaster: The Day When People Turned to the Library to Get the Latest News

The functions of the library in the community have varied considerably from the nineteenth century library to the present. On one occasion, the library was the prime locale for obtaining the latest, most updated news. Without radio, television, or computers to provide the latest breaking news reports, it was the library where Madisonians congregated to acquire the news they desperately sought. On Sunday, May 28, 1950, in celebration of the library's seventy-fifth anniversary, Julia Hopkins, chief librarian for the Madison Free Library from 1902 to1908, was interviewed in the Wisconsin State Journal. She recalled an incident in 1903 in which people flocked to the library to keep abreast of the latest news concerning their loved ones.

"In those days, people often had to turn to the library to learn what was going on in the world. On the day of the Iroquois Theater fire disaster in Chicago during the 1902 [sic 1903] Christmas holidays, Madison newspapers were swamped with frantic pleas for information from families whose young people had gone off gaily to attend a matinee in the new theater. The library volunteered to help get the bulletins out.

The newspapers rushed each piece of news to the library in the intervals between extra editions and we posted them on the bulletin board as fast as we could. I shall never forget that evening. The board was constantly surrounded by a crowd; I've never seen such intensity of feeling. Today, people would just turn on the radio to get the latest bulletins."

The first news of the terrible loss of life had reached Madison late in the afternoon: some 100 lives were lost. As the later reports came in, it was evident that the list of dead was growing. The telegraph offices were flooded with messages that evening as many anxious friends and relatives sought news of the horror and awaited answers to inquiries about loved ones who were supposed to attend the theater. Fourteen Madisonians, included a high school student and three UW-Madison students, were among the hundreds who lost their lives in the fire. The Madison Democrat described the death toll exacted by the fire as "a holocaust" and proclaimed "next to the Chicago fire, it is the greatest catastrophe" ever to occur in Chicago.

The fire erupted while Eddie Foy was performing in Mr. Bluebeard to an overflow crowd of more than sixteen hundred at a special holiday matinee in the new Iroquois Theater, a showplace of marble, plush and mahogany with an ornate lobby suggestive of an old-world palace. A haunting footnote to the history of the Iroquois is that the archway forming the stone front of the theater was a counterpart, except for minor details, of a monument that had been erected in Paris to commemorate the death of 150 victims in a flash fire at a charity bazaar in 1857. It had been a prophetic design.

When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, the librarians at the Central Branch of the Madison Public Library added a television to their staff lounge because they felt they needed immediate access to the media to keep abreast of the latest breaking news stories. Today, they log onto their computers when they want news updates.